|

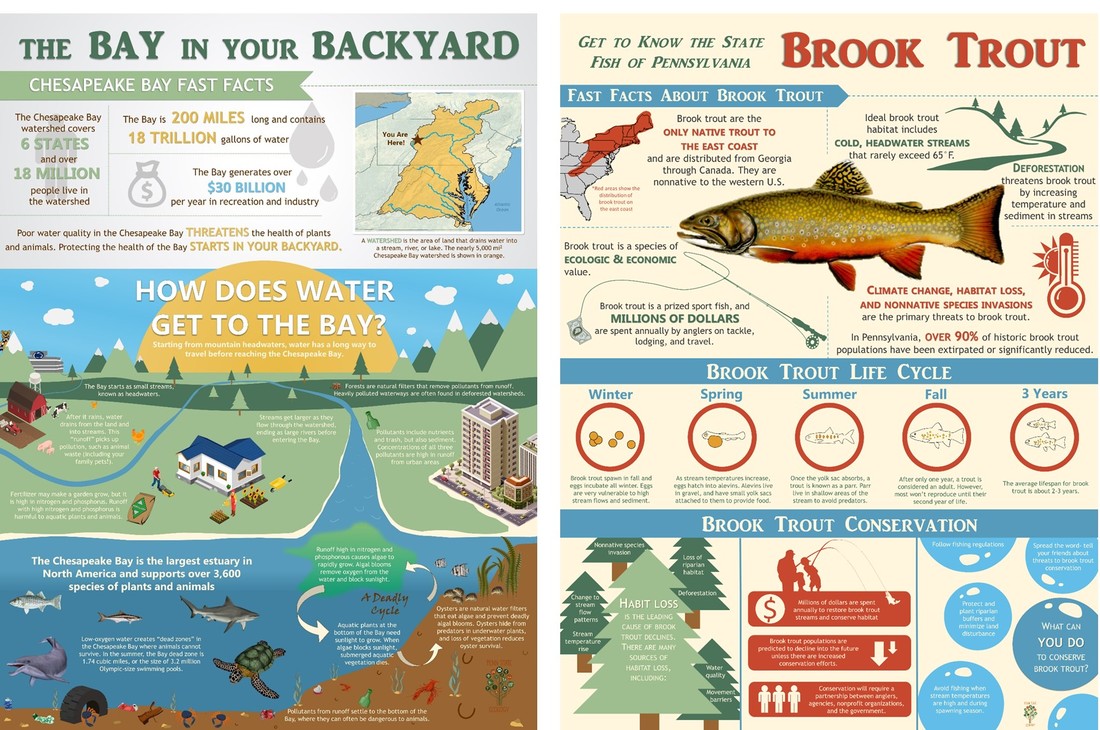

Time flies when you’re working on a dissertation. I turn around and it’s suddenly the end of the semester and I haven’t posted any updates in over a month. Oops. Truth be told, there hasn’t been a lot to update on recently. Preparing for outreach events had me spending more time photo shopping in Microsoft Paint than running data analysis in R. But, Ben and I put together some impressive posters, so I consider that time well spent. And, we showed them off this past week at an Earth Day event at the local elementary school.  Waterfalls are one way to stop introgression, but what other natural habitat features can decrease wild and hatchery interbreeding? Waterfalls are one way to stop introgression, but what other natural habitat features can decrease wild and hatchery interbreeding? I’ve also taken the show on the road, and have been visiting several chapters of Trout Unlimited to present the hatchery-wild brook trout interbreeding (or introgression) results that I discussed in a previous blog. At first I felt a little guilty about making introgression the main topic of my talk because I thought most everyone in attendance had already read my blog post. But, as science turns, after we submitted the manuscript for publication- and after we thought for sure we had covered all of our basis with analyses- reviewers unanimously wanted to see another analysis. Of course. Truth be told, we were actually happy to do the requested analysis. Simply put- they wanted us to quantify how introgression varies across different habitats. Is introgression higher in sites with higher temperatures? Lower pH? What about introgression rates in small vs. big streams? Does distance to a stocking location influence introgression? These are all great questions because they can help us understand if there are site-level characteristics that make a site more likely to have higher rates of introgression. And, if fish are more likely to introgression in certain habitats, then we can use that information to potentially adjust our stocking protocols. Unfortunately, while there was no doubt this analysis was worthwhile, we knew before we started crunching numbers that none of the results would be statistically significant. If you remember, less than 6% of all fish we tested showed signs of being introgressed. And, most fish at any of our 30 sample sites assigned to pure wild origin. Without the presence of introgressed fish in our study, we weren’t going to be able to find strong relationships between habitat and introgression. It’s like trying to quantify elephant habitat in Pennsylvania- if the elephants aren’t here, we can’t really quantify their habitat. But, because there are so few studies of introgression on stream trout, we knew that we could still use the results of the analysis to start building hypotheses about habitat variables that could matter. So, that’s what we did. We analyzed whether the probability of an individual being introgressed was related to eight “site-level” and three “watershed-level” habitat measures. The site-level variables includes measures of water quality and physical habitat that you would see if you were standing in the stream like pH, dissolved oxygen, and stream width (and we got lucky here, because all of that data was collected by Susquehanna University and the analysis would not have been possible without their willingness to share data). The watershed-level variables were those I measured back at the computer and were things like watershed area and landuse. Like we expected, none of our models implicated any of our habitat variables as a smoking gun that increases introgression- all models showed a statistically insignificant relationship between introgression and the 11 habitat variables. But, a bit to our surprise, we did have a few variables that approached significance. Again, this was surprising because we had so little introgression in our data, and so even a variable that trends towards significance is worth a second look. Probably not ironically, the variables that trended towards significant were also variables that have been suggested in other studies of lake-dwelling brook trout and stream brown trout as being modulators of introgression. It seems there is a consensus among studies that introgression rates are lower in larger streams, and at sites with low pH and higher adult brook trout densities. This makes some sense as higher wild trout densities increase competition (which likely decreases reproductive success of stocked fish) and larger streams have more stable flows that can help promote a large, healthy wild population. It’s suggested that pH might also be an important predictor of healthy wild trout populations, as macroinvertebrates densities are often higher in streams with higher pH. So, at this point, these results can’t yet be used to really direct stocking efforts. They really just point to a need for more directed studies of introgression in stream trout. But, it does make you think. Most of the time we only stock streams without brook trout, or in streams with “marginal” wild populations. Those “marginal” populations, which tend to be smaller in size but existing in decent habitat, may be the populations that are most vulnerable to introgression. So, by trying to avoid wild-hatchery interactions and stocking in marginal populations, could we actually be increasing the probability of introgression? Again, we just need more data to tell.

2 Comments

9/16/2019 04:15:46 am

I really have no idea what introgression is, but I am very much willing to learn. I know that you are also in the same boat as me, which is why I want to approach you. I think that it would benefit us both if we shared what we know to each other. I know that it might seem weird, but trust me, it is not. We need to be better, so why not try what I have in mind.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorShannon White Archives

October 2018

Categories

All

|

The Troutlook

A brook trout Blog

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed